Exporting a National School: Why Russian Galleries Struggle Abroad

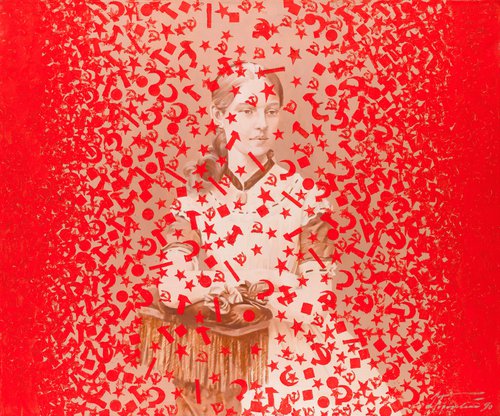

Searching Eye. Exhibition view. Paris, 2025. Photo by Ivan Erofeev. Courtesy of Alina Pinsky Gallery

While the 20th century saw Russian art galleries flourish as pillars of cultural authority in Western capitals, today’s dealers face a far more unforgiving landscape defined by sky high rents, globalized competition, and complex political tensions. Why does the “national export” model often falter abroad?

Despite the surge of interest in Russian art collecting since the turn of the millennium, and the expansion of a wealthy Russian diaspora across the West, few – if any – galleries specialising in the field have achieved lasting success outside Russia in recent decades, even before the current crisis. This stands in sharp contrast to the 20th century, when a robust network of dedicated galleries flourished across Europe and the United States. Spaces such as A La Vieille Russie in Paris, Galerie Gmurzynska and Alex Lachmann in Cologne, Ingrid Hutton and Ronald Feldman in New York, and Annely Juda Fine Art in London did far more than trade in works of art: they became cultural institutions, places where collectors could encounter, study, and develop a sustained understanding of Russian art. Having endured for decades, these galleries continue to command authority – whether still operational or not – their legacies now permanently woven into the fabric of Russian cultural history.

As globalisation accelerated towards the end of the 2000s, a new gallery model emerged. Rather than galleries from the periphery of the global art market establishing themselves in mainstream cities such as London and New York, it was the major international galleries – most notably Gagosian and Pace – that began opening outposts in new geographies, particularly in Asia, though notably not in Russia at that time. In Moscow, two gallerists stood out for their international reach and ambition: Volker Diehl and Gary Tatintsian. The latter was instrumental in introducing Damien Hirst (b. 1965) to Moscow audiences and remained based in Russia until 2022, before relocating to Dubai. These initiatives were designed to capture a new generation of collectors with aspirational tastes, drawn to internationally sanctioned artists with strong investment potential, while also incorporating a carefully selected representation of local practices.

In contrast, ostensibly hoping to capitalise on sales to the wealthy Russian diaspora in the West, and as well as looking for a slice of a bigger pool of international collectors, there have been several efforts by Russian gallerists to establish outposts abroad over the past two decades. These ambitions have not met with any longevity. Regina Gallery opened in London in 2010 and closed in 2013, pop/off/art opened in Berlin in 2012 and closed in 2014. This lack of local uptake has not deterred everyone – two years ago Igor Markin and his partner artist Liza Bobkova moved to London and planned to start a gallery business in the capital. They have since curated a few selling exhibitions in a trendy art cluster in West London, Cromwell Place, their inaugural show of Dima Filippov (b. 1989) followed by a show of new work by Bobkova herself. What challenges are they facing?

The quintessential Russian outpost in London was Vladimir Ovcharenko’s Regina gallery which opened to great fanfare in 2010 but just three years later it was closed down. Today Vladimir Ovcharenko sums up its fate in few words. He set up the gallery abroad having consolidated his own successful brand at home and that is crucial "otherwise isn’t it just like going to visit the sharks with your bare ass? They’ll eat you without even noticing”. There was also the sense perhaps that at home in Moscow at the time the market for contemporary Russian art was not strong leaving the whole exercise even more vulnerable to the ferocious demands of an alien and uncomprehending marketplace in London, with its astronomical rents, a crowded marketplace where you are vying for attention with gallerists who have been there for decades. In other words, how can you expect your guests to trust the table if the host refuses to eat from it?

I have good memories of the Regina Gallery’s London outpost where I used to attend all their openings, a stone’s throw from Sotheby’s on New Bond Street. They had an impressive roster of Russian artists which they exhibited in the centre of London in an atmospheric 19th century merchants’ warehouse and the gallery was cool, light and spacious. There were solo shows of artists like Oleg Kulik (b. 1961), Ivan Chuikov (1935–2020), Semyon Faibisovich (b. 1949) and Maria Serebriakova (b. 1965). Sad to see it go, its closure was also fortuitous for Ovcharenko in some ways, just before the political relations between Russia and the West soured irrevocably over Putin’s annexation of the Crimea.

Searching Eye. Exhibition view. Paris, 2025. Photo by Ivan Erofeev. Courtesy of Alina Pinsky Gallery

Were the huge overheads and saturated market the whole story? If the tried and tested ‘Gagosian template’ is to show international artists not presenting any specific national school but curated to show concepts, and styles over nationality, then Ovcharenko’s approach had an Achilles heel: the international artists he showed in Moscow were already represented by dealers in London, so to address this he decided to show Russian artists in London and international artists in Moscow. It was an approach that ultimately overemphasised national origins, rather than place the first impressions of collectors new to them on what it was that made these Russian artists great and important.

Back in the 20th century, some of the galleries promoting the Russian avant-garde and more unusually non-conformist Soviet art like Juda, Hutton and Dina Vierny who travelled to the Soviet Union in the early 70s where she discovered Ilya Kabakov (1933–2023) and Erik Bulatov (1933–2025), also connected it to the Western modernist canon, showing it as a forgotten or overlooked chapter and championing its pioneers, like Liubov Popova (1889–1924), Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) or El Lissitzky (1890–1941) many of whom even influenced the developments in Western European art, or at least were outstanding in the Paris school or within the context of German Expressionism.

It was perhaps easier for art galleries promoting Russian art to exist during the Cold War. Unlike today, the Russian avant-garde carried intellectual prestige without the contemporary political entanglement. In the post 2000s, Russian galleries entered Western markets at a time when competition was harder, audiences in London and Paris were more saturated, and political scrutiny was rising rapidly. Some initiatives were more educational than commercial, like Grad (2013–2019) and Erarta (2011–2016). In some respects both blurred the boundaries between a commercial gallery and a research based institution and neither were long lived, closing down by the end of the 2010s.

Today, the splinter between Russia and Western Europe means that it is virtually impossible for a Russian gallerist to set up a fully operational outpost in the West. Adapting quickly to harsh new realities, two gallerists formerly from Moscow have recently opened spaces in Dubai – Alisa Bagdonayte and Veronika Berezina. One outlier is Alina Pinsky, who last year bravely opened a dedicated space in the Le Marais district in Paris, her inaugural exhibition a group show of Russian artists on her roster including Igor Shelkovsky (b. 1927) which served as an introductory baptism of fire to the Parisian public. Moscow based XL Gallery one of the leading contemporary art galleries in Russia, is now supporting a Berlin based initiative called XL Projects Berlin, a kind of ad-hoc artist collective and communal space rather than a fully operational gallery. They have shown works by MishMash, ZIP group, Bluesoup, and Alexander Povzner (b. 1976) among others.

It is not the first initiative in Berlin by a Moscow based gallery. Pop/off/art opened a space in the city in 2012 with a solo retrospective of Gregory Maofis (b. 1970) but two years later it closed down. This coincided with the worsening relations between Russia and the West, as Sergei Popoff recalls “The decision to stop the gallery’s activites was driven by events in the Crimea, the general rise in anxiety and uncertainty about the future”.

If ‘cut and paste’ gallery outposts have not worked, faring better are more organically grown grassroots galleries, which build authority through quiet dedication over many years, like Ekaterina Iragui whose gallery business continues to evolve. Born in St Petersburg, she came to France with her American husband in 1992 and they were able to settle in Paris by virtue of her husband’s French grandmother. Iragui, a natural conduit to represent Russian art from inside, yet abroad, she has made a career of gracefully shuttling between Paris and Moscow. She started small, her first gallery was an informal closed space in her living room in Le Marais in 2003 where she initially showed French artists. Iragui’s name has become synonymous with Conceptual art, where she has successfully integrated a roster of Russian and international artists who share similar approaches, she now represents the estate of Nikita Alekseev (1953–2021). Today she has her sights set on expansion into the New York art scene, yet she continues to tread a cautious and considered path. Rather than committing to bricks-and-mortar expansion, she favours pop-ups and art fair participation, and – like many small-scale galleries navigating a period of global insecurity – has chosen to collaborate in order to manage costs. Her Paris space is shared with Veronika Berezina’s NIKA Project Space.

It seems that placing intellectual credibility before commercial ambition is important, and along with that a refusal to make Russianness a selling point. Galleries in China, South Korea and Latin America, once named emerging economies, have grown their own domestic market infrastructure to the extent that it has attracted international galleries to participate and invest in spaces, and not the other way around. And despite there being a large community of wealthy Russians in London, which has diminished a lot over recent years, there are no major Russian gallery initiatives that have endured there and built a legacy on the ground. Perhaps a gallery promoting Russian art feels too provincial for a community of rich people who live an exceptionally cosmopolitan life and whose children go to schools and colleges in the West.

But context is key. Maxim Bokser a respected Russian art authority, a creative personality who is part of the contemporary Russian art scene, has done numerous initiatives in the West to promote and sell Russian contemporary art, and now has a dedicated space in the centre of Riga. Coming at a time when many creative Russians have moved abroad, there is always the sense that this may be transitional. When I visited him there last winter to me it felt like a sanctuary, but the truth is that local audiences are not receptive. Now he has adapted by showing works by young Latvian artists and continues to look at collaborating with artists who live between two or more cities, creating a safe space for the displaced. How successful this will be in the long run pales into insignificance with the importance that his initiative has for artists who desperately need not just material but moral support.

For gallerist Igor Markin and artist Liza Bobkova leaving the comfort of their well-established life in Moscow, they may have made judicious first steps in the shark invested pool of the London art world. Rather than investing in real estate or paying sky high rents, in the boutique West London gallery cluster where they have done some well curated projects, they are close to other local galleries and a readymade clientele. All they need now is a handful of good international artists and a lot of patience.