Dmitry Kovalenko: a collection that formed itself

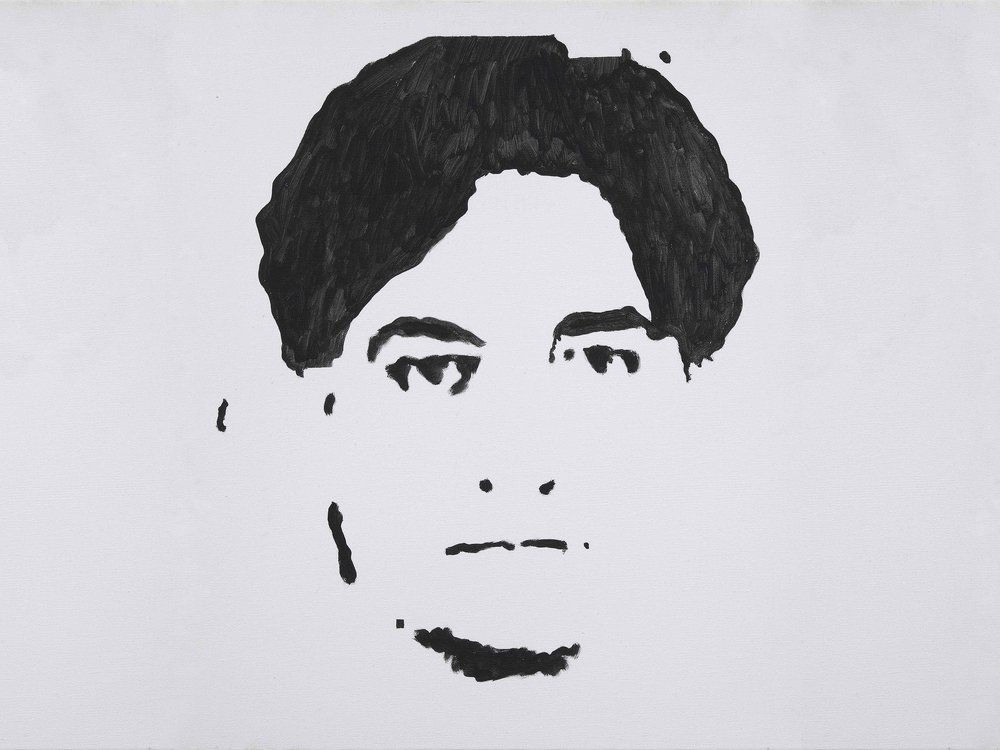

David Ter-Oganyan. Dmitry, 2005. Acrylic on canvas, 59.8x50 cm

Moscow businessman and art patron Dmitry Kovalenko, the scion of a long line of Russian artists, swears that his collection created itself, without his interference.

By all rights, Dmitry Kovalenko could have been an artist himself. He was born into a family that unites several dynasties of Russian artists and he grew up in their studios, so much so, that in his eyes, one of Moscow’s leadings museums very much resembles a portrait gallery of his own family. Nonetheless, he took a different path and built a business with his wife as a consultant to Italian companies. However, the end result was still art.

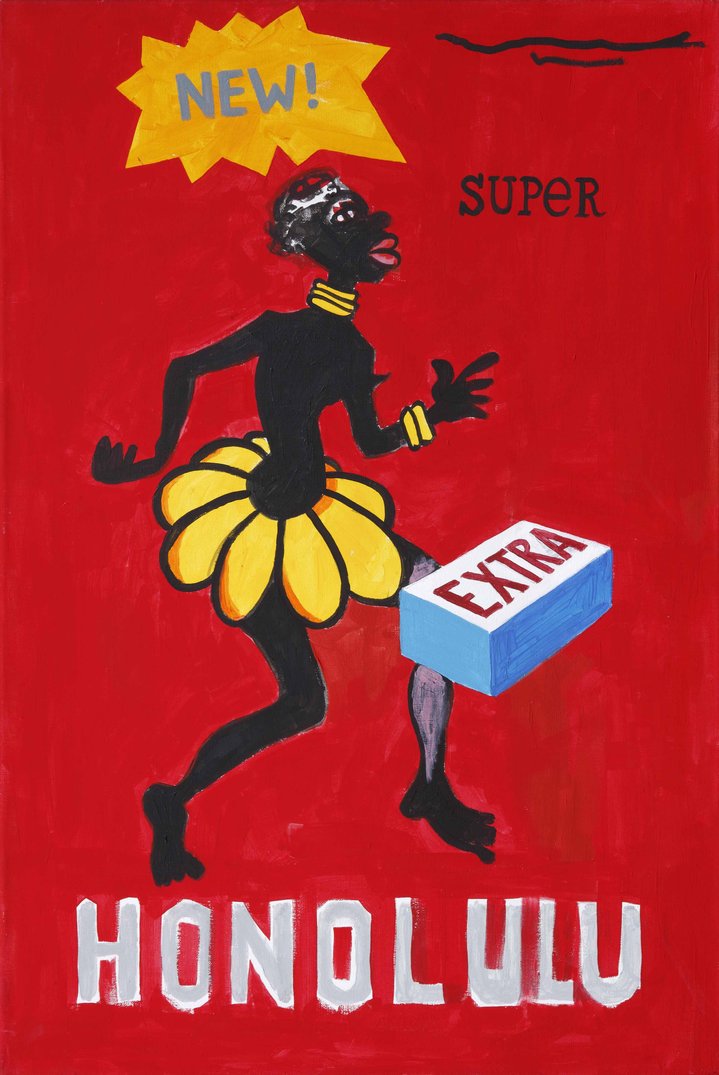

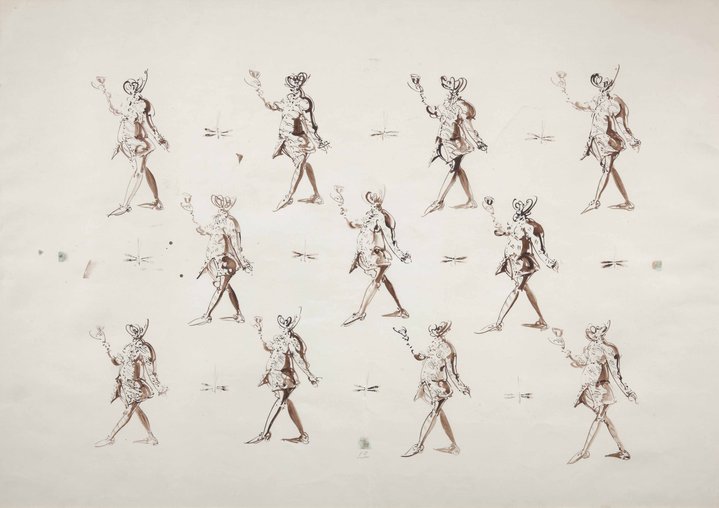

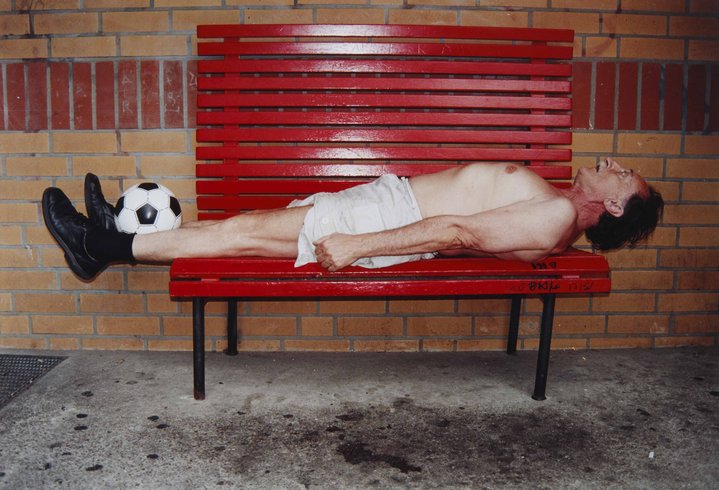

Since the 1990s, he has accumulated one of Russia’s best collections of contemporary art, which numbers nearly 700 works. They include many by Vladimir Dubossarsky (b. 1964) and Alexander Vinogradov (b. 1976), as well as Konstantin Zvezdochotov (b. 1958), Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe (1969–2013) and younger artists, such as Anya Zholud (b. 1981).

Much of his collection hangs on the walls of his office situated in what used to be one of Moscow’s industrial zones. “For me, this is my usual milieu as there were always paintings around me since childhood,” he said. “It’s more pleasant than a bare wall.”

Some 200 of this collection’s works will be on display in the New State Tretyakov Gallery’s West Wing, the very institution whose content so vividly reminds Kovalenko of his own family. However, the exhibition’s opening also depends on when the coronavirus quarantine can be lifted.

It takes thick tomes and extensive family trees to sort through Kovalenko’s background, which includes one of Russia’s most popular painters, Valentin Serov (1865–1911), his great-grandmother’s cousin. One of his great-grandmother’s sisters posed for ‘Girl in the Sunlight’, a portrait by Serov. More immediately, his great-grandfather was Ivan Yefimov (1878–1954), a sculptor and theater designer, while his great-grandmother, Nina Simonovich-Yefimov (1877–1948), was a painter, graphic and puppet artist.

In the 1930s, Yefimov and another relative, Vladimir Favorsky (1886–1064), an artist known for his woodcuts and book illustrations, were allocated to create an art studio on the outskirts of Moscow. Known as the “Krasny Dom” (Red House), this magical shelter from reality is still going strong to this day and the descendants of the original founders continue to create in it.

That heritage guided Kovalenko, who has an eye for beauty. His guide in the world of contemporary art has for many years been Elena Selina, curator and director of XL, one of Moscow’s oldest and most prestigious galleries. Selina is also the curator of Kovalenklo’s Tretyakov exhibition, which will present the works in alphabetical order, listing artists by their surname.

“From my childhood, I was surrounded by paintings and sculptures of my relatives. In the early 1990s, galleries started to open in Moscow and this became the contemporary art scene,” he said, mentioning early gallery owners such as Marat Guelman, Aidan Salakhova, Vladmir Ovcharenko and Selina. “I helped them when they opened (their galleries). There were expenses. They had to print catalogues and stage exhibitions,” he says of those early days and the start of his collection. “My first (art) works were their way of thanking me for my help.”

“It wasn’t my goal to create a collection,” he says. “It collected itself, in a natural way. I first supported one gallery and its artists, then another. Not all of them, only the ones I liked.”

The result was that Kovalenko got to own some of the best pieces created by Vinogradov & Dubossarsky (then a duo, but which has since split). Kovalenko also got hold of early works by Yelena Yegalina (b. 1949) and Igor Makarevich (b. 1943).

Once his collection, which focuses almost exclusively on the 1990s and the 2000s, started expanding, Kovalenko began to seek out specific works.

“When I choose a work, the main thing for me is to hang it on a wall and to want to look at it, for it to be beautiful, for it to be pleasing to look at, and for it to have a certain kind of energy. This is how my collection was formed,” he explained. It is also a completely non-commercial collection. Kovalenko does not deal in his works and does not expect them to increase significantly in value. “I never looked at it as an investment, but always simply for the sake of beauty,” he said. Having already got some of the best works of older Russian contemporary artists, he says that in order to be drawn to purchase something by new ones, “they have to amaze me”.

Kovalenko has never collected Western artists. However, he plays a role in promoting Russian art in the West as a member of Tate Modern’s Russia and Eastern Europe Acquisitions Committee. “It is for the development of Russian contemporary art,” he says.

From A to Ya. Exhibition of Dmitry Kovalenko’s Collection

Moscow, Russia

11 April – 10 May 2020