Co-Author or Assistant? When Artists Argue over Authorship

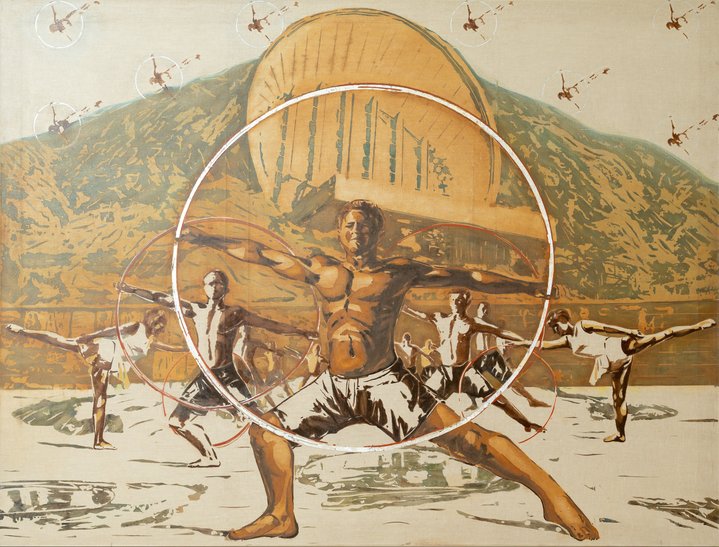

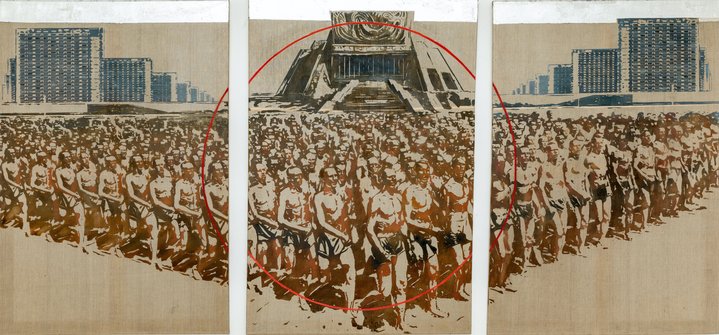

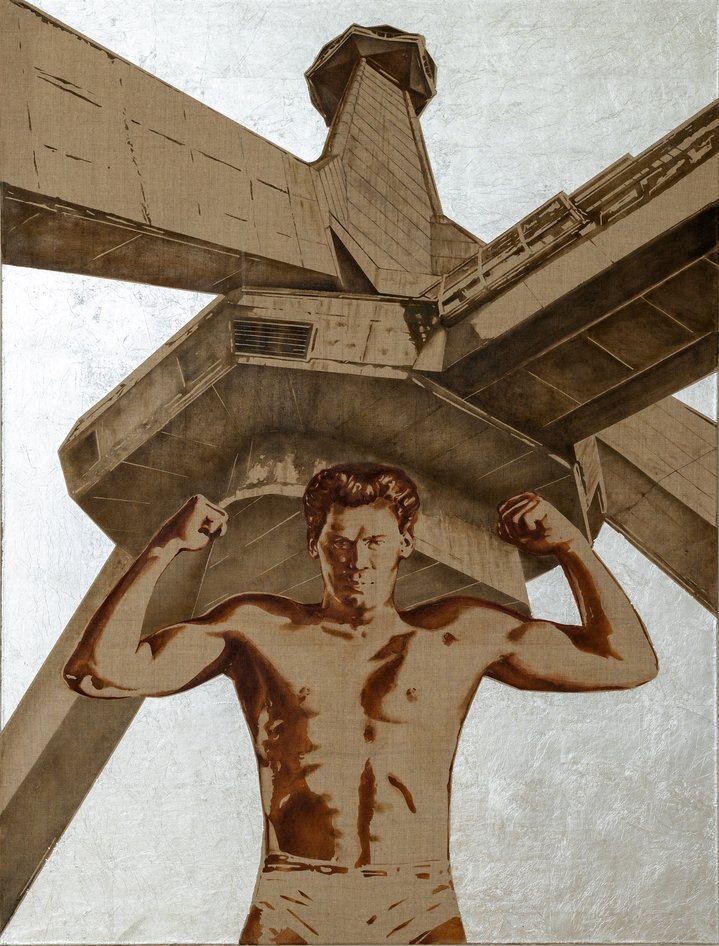

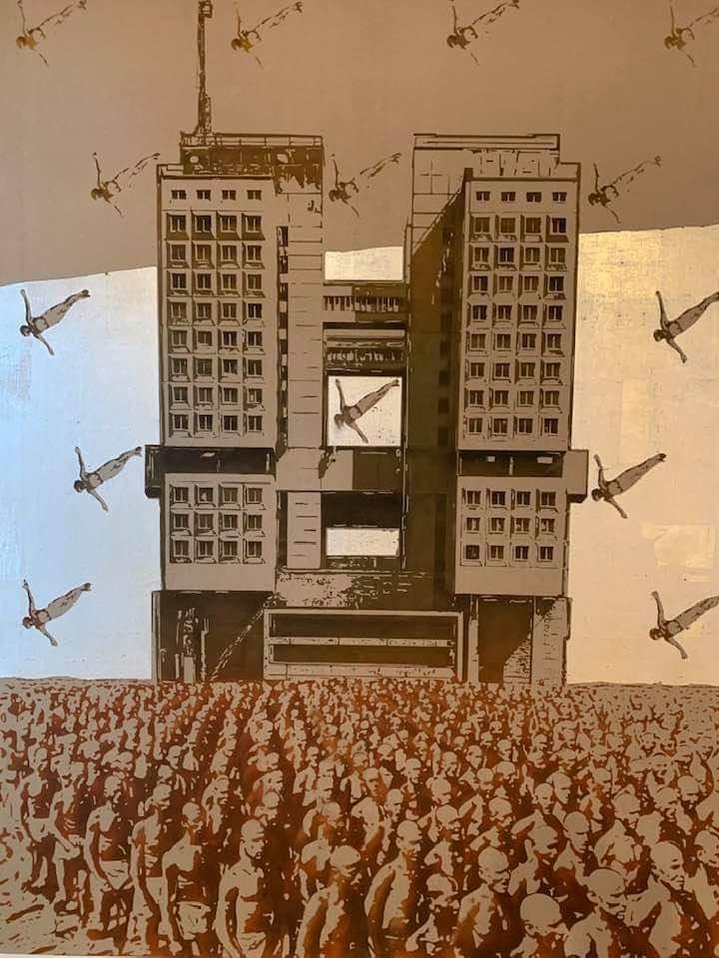

Ilya Evdokimov, Valery Ulymov (?). Radiation, 2019. From the series 'History of the Future'. Photo courtesy of Ilya Evdokimov

Neither AI artists nor painters are immune to the plague of authorship disputes. Recently, a controversy over AI-generated work went beyond the borders of the art community, while a less publicized conflict between two painters continues to simmer even after its legal resolution.

In the art world, authorship disputes are nothing new. One of the most recent cases between art dealer Marat Guelman (declared a foreign agent by Russian authorities) and Evgeny Nikitin, an Israeli neural networks guru is doing the rounds on social media, rekindling once again the public’s interest in the subject of authorship in the field of visual art.

This is a particularly fascinating case because none of the three parties in the dispute have ever been or even claim to be an artist. Marat Guelman commissioned prominent Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin to create a series of artworks based on his novels with the help of AI. Working with neural networks is so complex that he subsequently hired Evgeny Nikitin to turn Sorokin’s ideas into prompts for the AI-powered software. So far so good. However, when Nikitin accepted the offer with its modest 500 Euro fee, it was on the condition that his input would be acknowledged at the exhibition. Guelman who was reluctant to call him a co-author came up with a term ‘prompt engineer’ but during the opening of the exhibition his name was not mentioned. Feeling disappointed, Nikitin took to social media writing a series of posts in which he described his input and the whole process of creating images with the help of AI. It transpired that he was happy with the term ‘prompt engineer’, yet many other posters commenting on the subject suggested that the real author of the works might not be Sorokin, but Nikitin himself. Many others believed that the series was co-authored by Sorokin, Nikitin and the authors of the AI-based software which was used in the project.

The discussion was a reminder, if we need one, that today artists are not the solitary geniuses in a garret who make art with their own hands. Assistants and apprentices often are the ones applying paint to canvases, or, if you like, type prompts on a screen. It is nothing even remotely new, artists such as Leonardo de Vinci, Raphael and Tiziano each had their bottega with more than a few trusted apprentices helping the master to work on important commissions or handle the sheer number of commissions impossible for one artist to execute alone. Rembrandt’s scholars constantly attribute and re-attribute works from his enormous oeuvre either to the master himself or to his studio, and the other way around. And this tradition continues today, perhaps on and even larger scale: at his peak, British artist Damien Hirst employed up to seventy assistants, while Takeshi Murakami reportedly has two hundred!

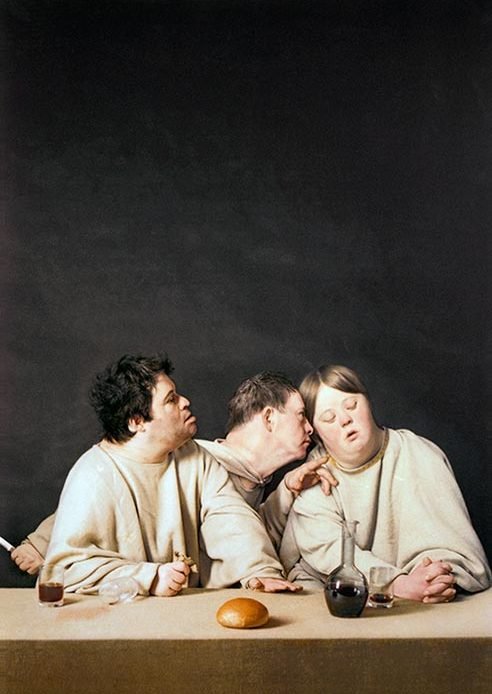

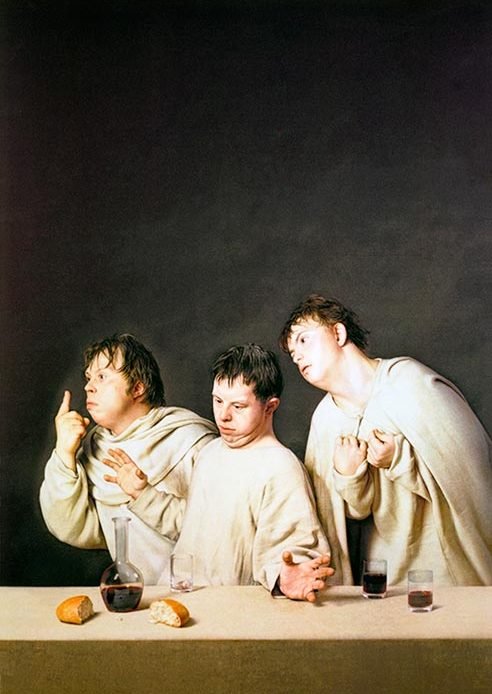

So far so clear, but confusion sets in where the boundary between an assistant and a co-author is elusive, and ultimately in some cases this can be disputed by the artists themselves. In Russia in the 2000s, artist Evgeny Semyonov (b. 1960) and photographer Rauf Mamedov (b. 1956) argued over the authorship of a critically acclaimed series of photographs consisting of people with Down syndrome re-enacting episodes from the New Testament. Each of the two artists claimed independently that the series was his solo project, although Semyonov acknowledged that he had hired Mamedov as a photographer to bring his idea to reality. This kind of issue was even thornier in the case of the Collective Actions group, famous for their outdoor happenings and numerous texts. This reached a peak in the 2010s when a former member set about to quantify the input each of them had made to the entire oeuvre of the group - as an exact percentage.

However, conflicts are also rife among artists who work in more traditional media. One is currently simmering over the ‘History of the Future’ project. This series of paintings, inspired by Soviet propaganda imagery and Brutalist architecture, was conceived by artist Ilya Evdokimov (b. 1973). He had sent an application with a detailed description of his project to Moscow’s State Central Theatre Museum named after A.A.Bakhrushin and had almost forgotten about it when a reply arrived as a pleasant surprise. The museum generously offered him four halls in the museum for a solo exhibition. However, at the time the artist only had one painting ready and he needed sixteen to fill the space and the deadline was tight with the opening date set in six weeks. Evdokimov asked a personal friend, artist Valery Ulymov (b. 1980) to help him paint the works based on his sketches.

They worked together in Ulymov’s studio, often taking turns in painting the same canvas. According to Evdokimov, Ulymov wanted to be described as co-author, his name mentioned alongside that of Evdokimov. Evdokimov had agreed but only on the condition that Ulymov would show the works to two of his influential acquaintances Aidan Salakhova and art dealer Elena Selina and try to persuade them to become curators of the project. This never happened. The exhibition posters had the names of both artists but by this time Evdokimov had become dissatisfied with Ulymov’s contribution. “Once, while we were both working together in the studio, he made a comment that he felt the paintings were not worth showing to Aidan, that they looked like wine labels! I realized then that he did not really believe in that project”, Evdokimov told Art Focus Now. In fact, this was not the only grudge he came to harbour. Ulymov went on holiday soon after they started working on the paintings and he posted three paintings on his Instagram account without mentioning Evdokimov’s name or asking for his permission. There were also some issues over bent stretchers of the canvases. Evdokimov still sees himself as the only real author of the works and Ulymov's role as being purely technical – one of assistant, not co-author. After the exhibition, Evdokimov divided the paintings equally between them and they signed a legal agreement that the artworks would always be exhibited under two names. Evdokimov now considers this agreement ‘wrong’ and regrets having concluded it. Valery Ulymov did not respond to Art Focus Now’s requests for comment.

Since then Evdokimov has held more exhibitions under his name only (one is open until 28th of November at the Q-Art Gallery in Moscow) and he has continued to work on the ‘History of the Future’ series and included new paintings, made all by himself, in these exhibitions together with the original ones. According to Evdokimov, Ulymov has exhibited works which were made jointly without mentioning his co-author – he saw some of them on exhibition at the Cube art centre in Moscow last summer and asked that they were removed from display.

Despite their written agreement, the question of who exactly the author of the first sixteen paintings was, has never been completely resolved. “From a legal perspective Evdokimov is the sole author, as he has in his possession sketches which confirm his sole authorship,” art historian and expert Uliana Dobrova, PhD told Art Focus Now. “As for the reputational costs, I think Evdokimov is the injured party. From a moral point of view, you could say that he was generous towards a colleague by including him as a co-author,” she added. Lawyer Julia Verbitskaya, a partner in Verbitskaya, Schastlivy and Partners Law Agency begs to differ. “By Article 1258 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, artists who have created a work or a series of works by joint creative labour are co-authors, regardless of whether this work forms a single whole (in this case each of the paintings), or consists of separate parts, each of which has an independent meaning (collage, installation, a single exhibition project),” she explained to Art Focus Now. “Thus, regardless of whether the artists are satisfied with each other and whether they have hired the necessary curators, if they both, artist Evdokimov and artist Ulymov, were creatively involved in the making of the works, neither of them can be arbitrarily deprived of their authorship. They have equal rights, which they share and realize together,” says Verbitskaya. She stressed that neither of the co-authors may prohibit the other from exhibiting the works they created together, especially if, as a result of the agreement reached, part of the co-authored artworks has been given to one artist, and the other part of the work has been given to the other. “However, indicating that the work was co-authored, by two artists, Ulymov and Evdokimov, is a requirement which, according to the law, must be complied with.” Yet, according to the lawyer, the artists should share the praise for the work, but not the financial rewards: “As for income from copyright or other rights in rem, it is to be transferred to the artist to whose ownership the co-authored work was transferred”. Dobrova notes that issues around authorship/co-authorship are sensitive for the market. Even an impressive history of sales as a duo does not guarantee the same level of prices for each of their participants, once they decide to part ways. “This is where a record in a database such as the Russian-language portal ArtInvestment.ru is important since this is the information that appraisers and experts like me use in the future,” she says. “Regarding Ilya Evdokimov, fortunately for him, he has an independent record in the database. And a pretty good result: in 2021, his painting ‘Soaring’ was sold for 295,000 roubles at Moscow’s Art Investment Auction house” ($4,012 dollars at the rate of the time – Ed.).