An epidemic of Russian fakes

The forgery industry, whose prices are irresistible, keeps fooling gullible lovers of Russian Avant-Garde. In a recent series of widely publicized scandals, the forgers’ tricks have been exposed by experts. These cases should serve as a warning for collectors.

The “World’s Oldest Profession” is a title that belongs to a different money-making industry, but art forgers are close runners-up. They follow art as night follows day and they will never cease to exist. In September 2020, the forgers will get their moment of glory, thanks to an exhibition at Cologne’s Ludwig Museum called ‘Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: original and fake. Questions, research, explanations’. It is not the first time that fakes have gone on show as such in museums, but it should also shed a spotlight on a whole fake industry that has mushroomed since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Ludwig has in storage some 800 works of that extraordinary period of Russian art, 100 of which are paintings. Many were donated to the German modern art museum and they will all undergo an in-depth investigation whose results will be published this autumn. The curators promise sensations. New techniques that can identify dubious attributions will be presented and a parallel conference on fakes and how they manage to appear in serious collections will also take place.

It was largely the wall of secrecy built over 70 years of Soviet rule that created the conditions which made it possible for Avant-Garde fakes to proliferate after the empire’s collapse in 1991. The fake industry is of course universal, but when the Soviet Union crumbled, everything suddenly became possible in what had so long been a hermetic and tightly controlled country.

Russia had talented artists, who had for years trained how to paint by copying the classics. It is a tradition that still continues and it is the schooling an artist needs, in order to turn into a good forger. What helped to make those forgeries more credible was the chaos created by revolution, wars and the many other upheavals of Soviet rule.

Such a background made it easier to concoct credible legends about an artwork’s non-existent provenance, although that issue does not seem to be a major concern for those ready to buy what the forgers are offering. Most of the buyers who accept those offers simply cannot resist the chance of obtaining a great name at a major discount to its normal cost. Greed can rarely resist a bargain.

A great deal of what is now known as the Russian Avant-Garde was scattered over more than 100 provincial museums after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. It was only in 1928 that orders were sent from Moscow to remove from public sight the masterpieces which had been renamed ‘Bourgeois Art’.

The fate of those condemned works ultimately depended on what risks museums were ready to take in order to save banned masterpieces. Brave museum staffers hid those works in the remotest vaults and these only saw the light of day again once communist rule had ended.

The first museum to have made its fakes public was one in Rostov Veliky, a three-hour train ride from Moscow, which staged a 2018 exhibition of what it determined as eight forgeries. Its story is a microcosm of the impact of Stalin’s cultural policies. In 1930, ‘Comet’s Tail’, the last painting by the Avant-Garde artist Olga Rozanova (1886–1918), was de-listed from the museum’s inventory and is believed to have been subsequently destroyed. However, who knows its fate for certain?

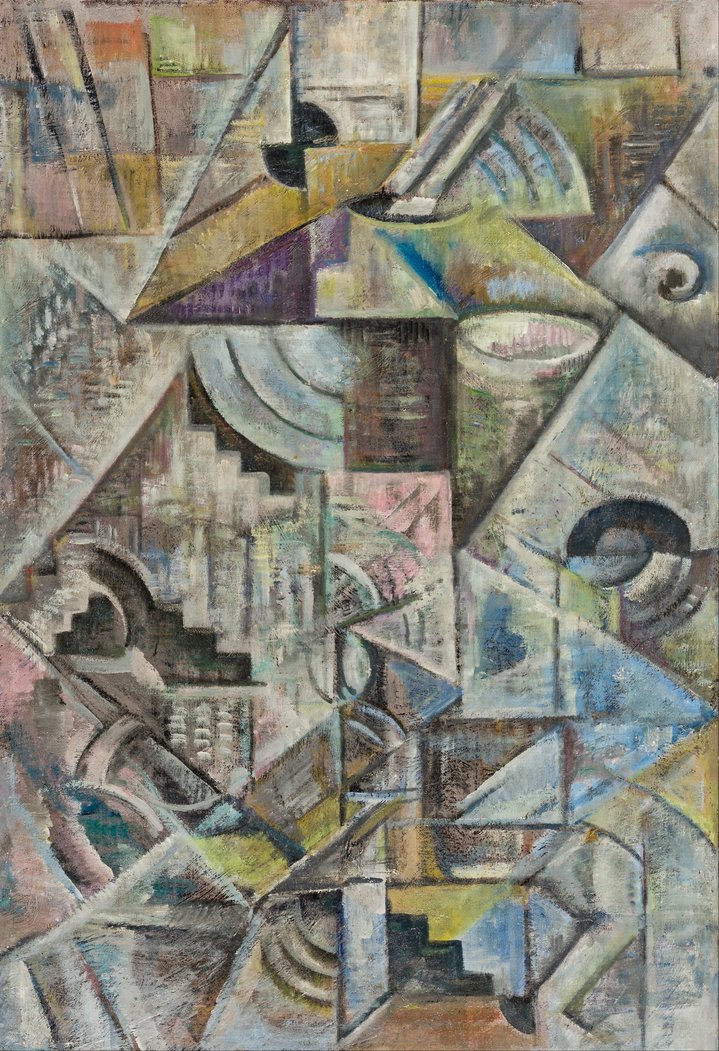

That museum’s two most important fakes, as reported in the December 2018 issue of Russian Art Focus, are ‘Samovar’ by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) and ‘Non-Figurative Composition’ by Lyubov Popova (1889–1924). The museum now believes both were stolen “not earlier than in the 1960s” and replaced by forgeries.

There is an identical Popova painting the Thessaloniki Museum that now houses the collection of the great Greek-born Moscow collector George Costakis (1913-1990), but its director has said it is definitely not the one missing from that Russian provincial museum.

As for the Malevich, MoMA’s own ‘Provenance Research Project’ has identified the ‘Samovar’ in its collection as having been “transferred to the Museum at Rostov-Yaroslavsky in 1922, sold at a Sotheby’s London in 1972” and “acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1983, from the Riklis Collection of the McRory Corporation”. That description perfectly matches the Russian museum’s missing ‘Samovar’.

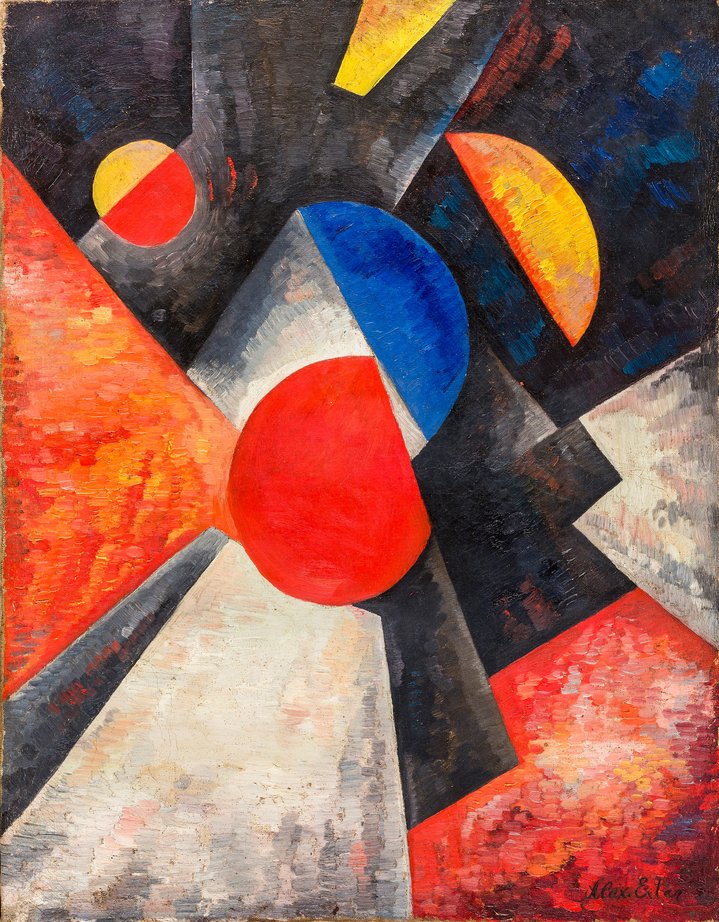

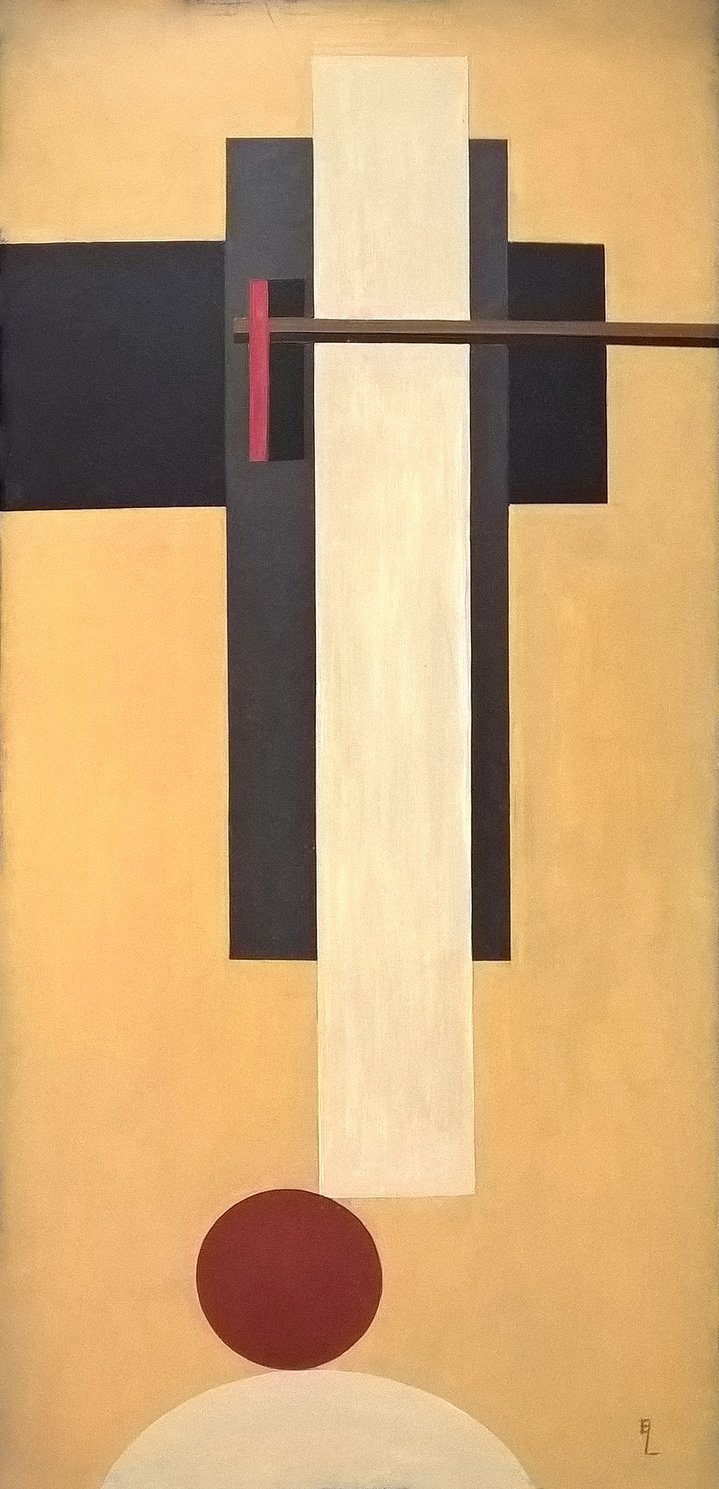

The loudest, most recent scandal involving Russian fakes was sparked by an exhibition that opened at Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts in October 2017, which supposedly showed 24 previously unknown works of Russian Avant-Garde. The exhibits claimed to show works by Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), El Lisitsky (1890-1941), Nikolai Larionov (1881-1964) and Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962).

The works were part of the collection owned by Igor and Olga Toporovsky, a Russian couple with a castle in Belgium. The exhibition was closed after 11 major international experts and art dealers wrote an open letter to the authorities denouncing the exhibits as fakes. As a result, Catherine de Zegher, the Ghent museum’s director, lost her job.

In February 2019, the Belgian authorities launched an investigation and Toporovsky was arrested in December of the same year on allegations of fraud, money laundering and trafficking in stolen goods. An article published in the Russian newspaper Izvestia, claimed Russian detectives had been wanting to question Toporovsky for the last 15 years and had a hand in unveiling the alleged scam.

A 13 February 2020 article on “how Igor Toporovsky sold paintings and who bought them”, published on the website of The Art Newspaper Russia, told the story of how a Russian businessman named Alexander Gordon, had bought 18 paintings from Toporovsky for a total of USD 1.55 million in 2005. Experts later ruled they were all fakes.

The art world recently hailed as a major victory the acquittal of prominent British dealer of Russian art James Butterwick in a libel case brought against him in Italy after he described as “an absolute disgrace” a three-month-long exhibition called ‘Russian Avant-Garde from Cubo-Futurism to Suprematism’. The show opened in the Italian city of Mantua at the end of 2013.

The exhibition’s organizers filed a civil lawsuit, accusing Butterwick of damaging their business reputation. However, an Italian judge ruled that “Butterwick expressed an opinion based on his proven and recognized competence and experience, which, although strongly stated, was never offensive or unfounded”. Butterwick was one of the 11 signatories of the letter sent over the Ghent exhibition.

The moral of this story is that the ancient Roman warning “Caveat emptor” (Latin for “Let the buyer beware”) remains as relevant today as it was in the days of Julius Caesar.

This article was based on a text published in the March 2020 issue of

The Art Newspaper Russia.

Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations

Cologne, Germany

26 September 2020 – 3 January 2021