An ebullient collector and his silent partner

Philanthropy and art are inseperable for Vladimir Smirnov and the contemporary art collection and foundation he built together with Konstantin Sorokin, a corporate colleague who prefers to keep a low profile.

Vladimir Smirnov is a down-to-earth art collector who likes to call a spade a spade. When he buys a work from an artist, he bargains and insists on getting more than the usual 10 percent discount, but says he always pays immediately.

More importantly, he has strong views on a collector’s responsibilities. “There are people who are involved in art, but not very involved in philanthropy. I don’t really understand how it’s possible to be involved in art without being involved in philanthropy.” It is something he regards as “the most insufficiently developed important issue in our country, which also affects the development of art”. Smirnov says art accounts for about 10 percent both of his activities and his budget.

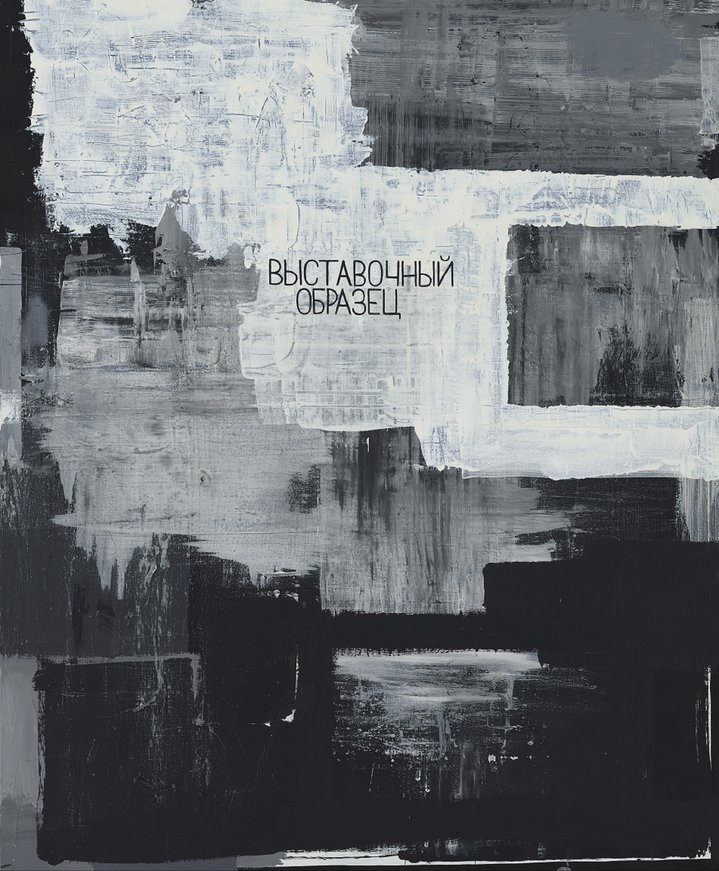

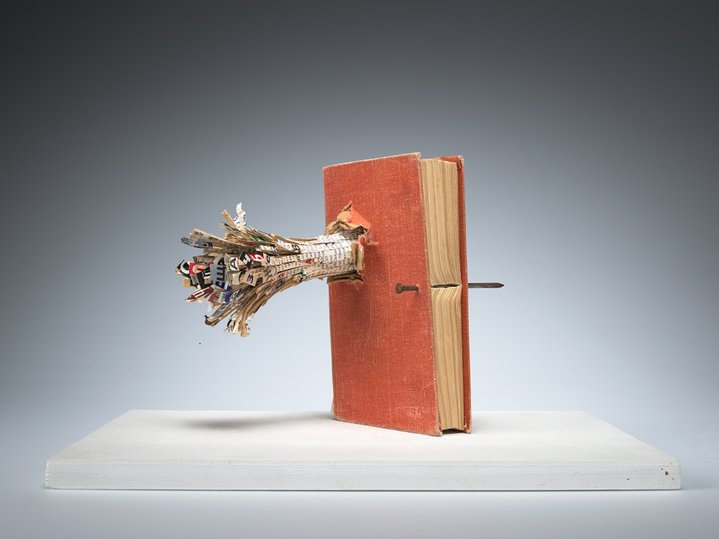

Smirnov and Sorokin donated over 100 works of 21st century Russian art to Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery in October 2019, enabling that museum to establish a high-level collection covering that period. In February 2020, they presented another 30 works to the same museum. Until those donations, it had owned almost no art works created after the year 2000. “It’s a beginning, a signal to other collectors and institutions that we should help the biggest museum of Russian art to start forming history today,” Smirnov explained.

An exhibition of the works the pair had given was indefinitely postponed due to COVID-19, the epidemic which has shut down all Russia’s museums.

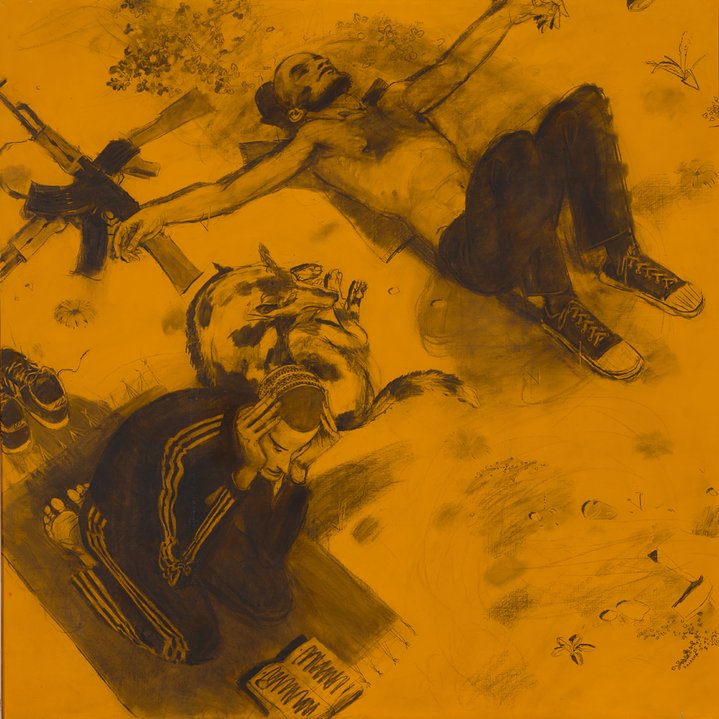

Smirnov and Sorokin were initially guided in art collecting by Pierre Brochet, a Moscow-based French collector, who amassed an earlier generation of artists, such as Vladimir Dubossarsky (b. 1964), Valery Koshlyakov (b. 1962) and Timur Novikov (1958-2002). That collaboration ended amicably.

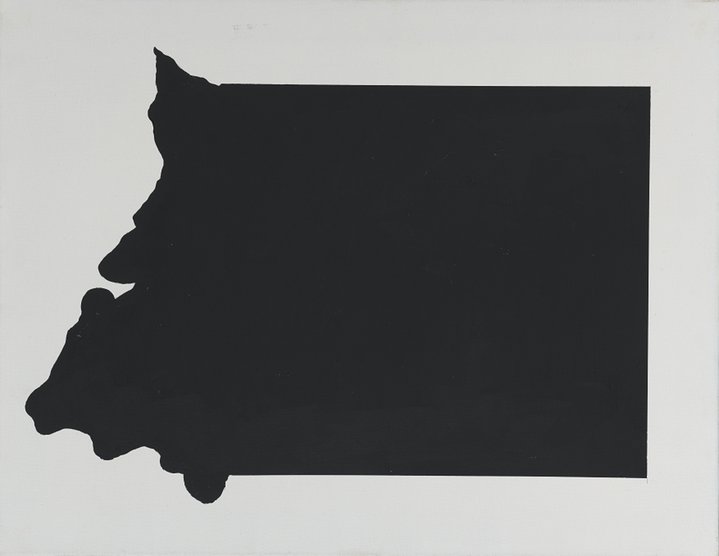

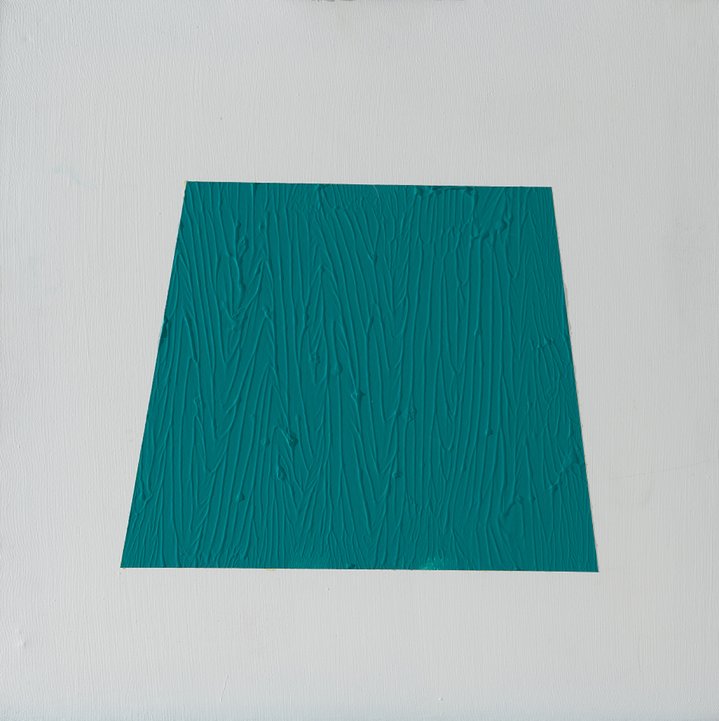

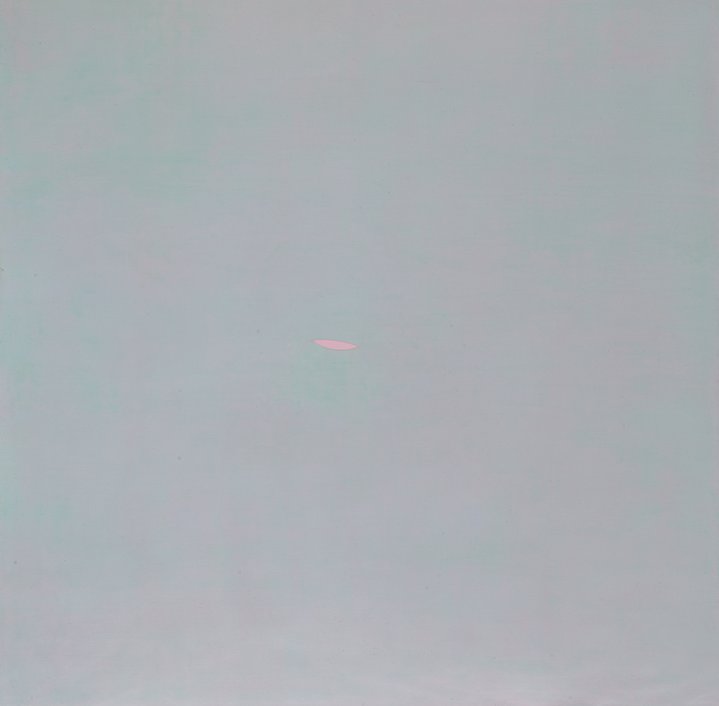

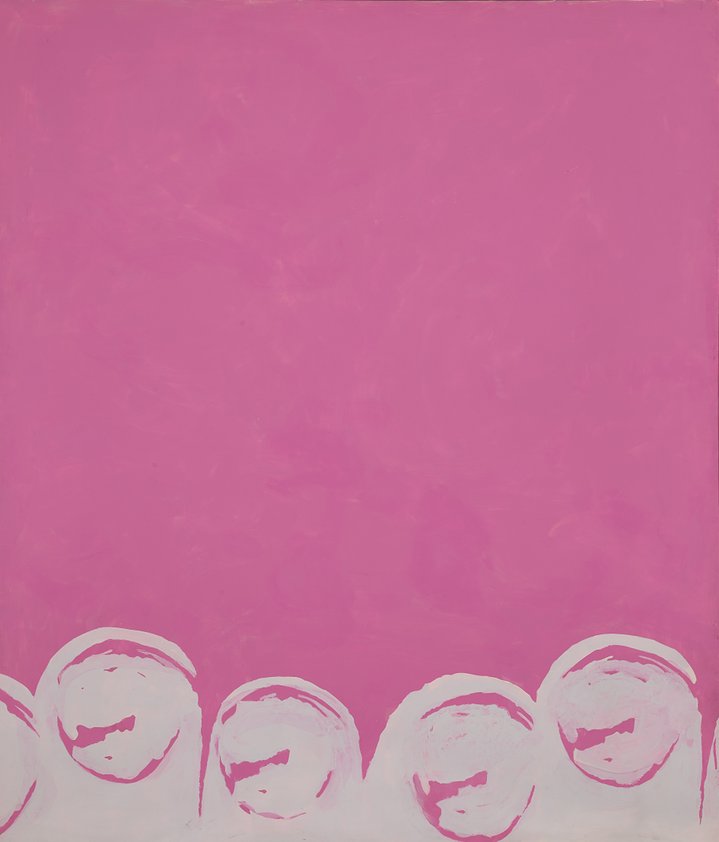

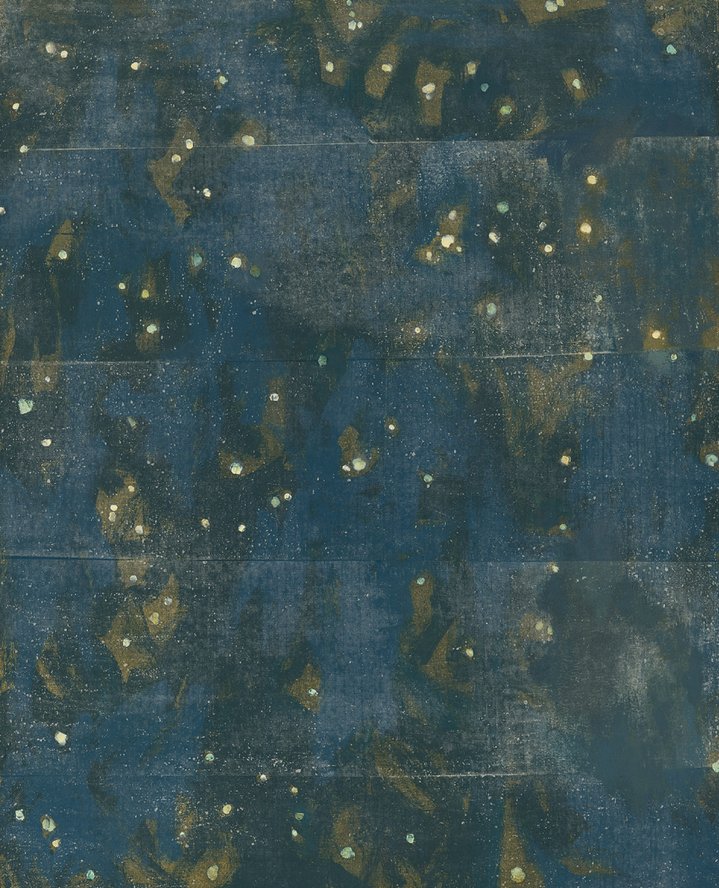

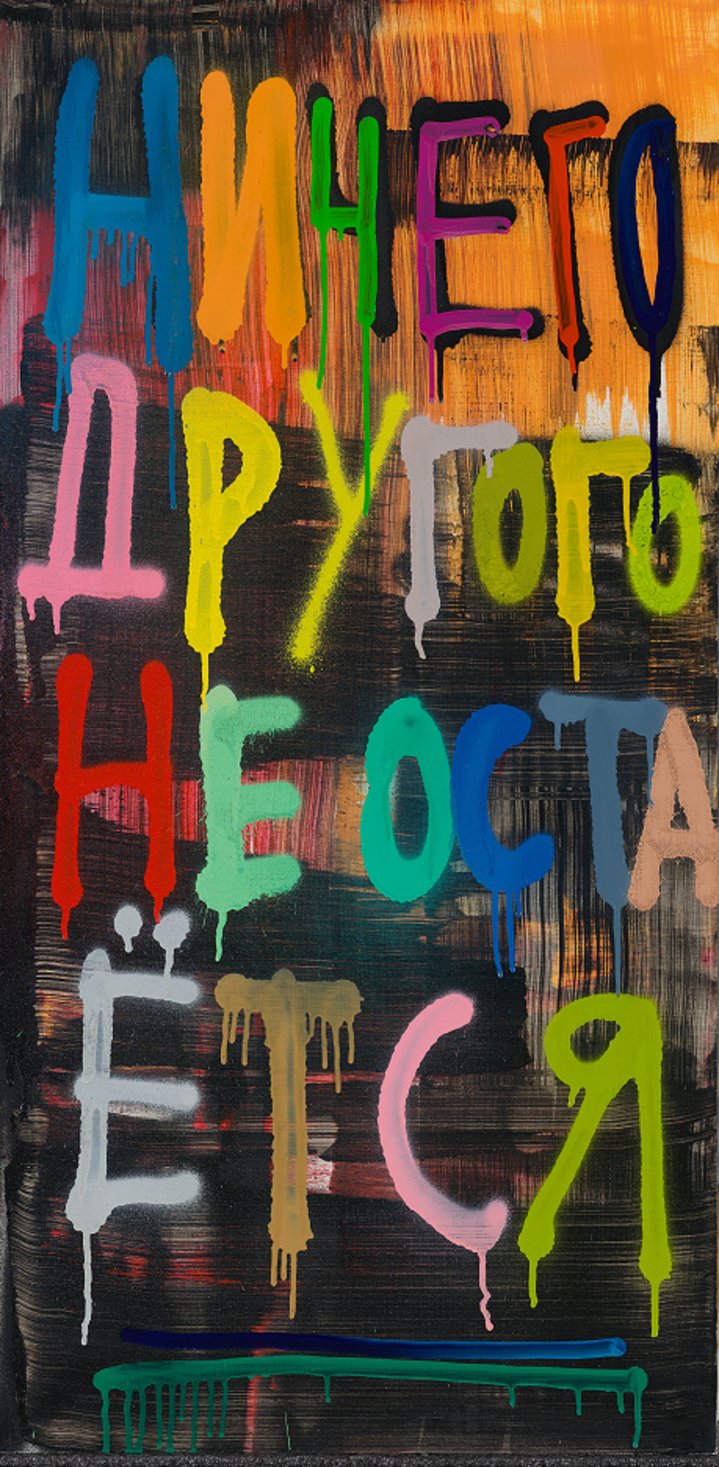

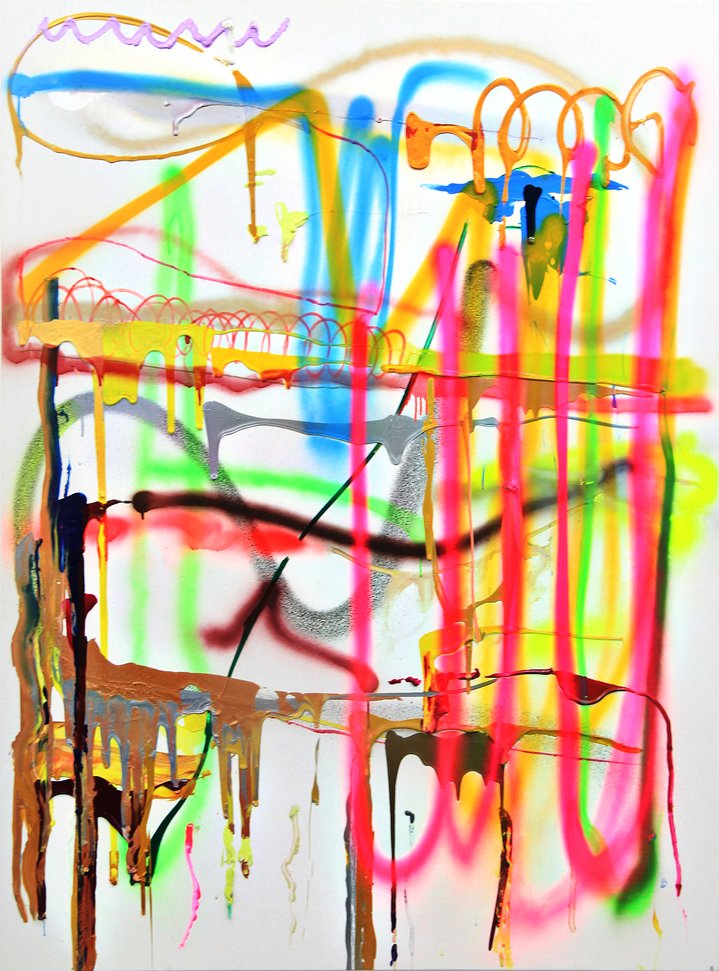

Teresa Mavica, director of gas billionaire Leonid Mikhelson’s V-A-C Foundation “directed my attention to young artists”, such as David Ter-Oganyan (b. 1981), Sergey Sapozhnikov (b. 1984) and Alisa Yoffe (b. 1987), Smirnov says. “Then came development of other artists,” such as Misha Most (b. 1981), initially known for his street art, and Valery Chtak (b. 1981). “It started with this small group. I noticed them and I liked them,” Smirnov added.

Smirnov, who was born in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, began to work with Mikhelson in the late 1980s, long before that businessman’s giant natural gas company, Novatek, “was even an idea”. Sorokin was also a senior executive. Smirnov regards Mikhelson as one of the people who shaped his life. The two of them talked about art and went to exhibitions together, but Smirnov says he did not seek Mikhelson’s advice on creating the collection.

“I used to go to museums very rarely before,” Smirnov confessed. “After the age of 40, I started to become more interested in art, theater and ballet,” but he added he was against obsessively “going to all of the Friezes and FIACs, racing around everywhere wide-eyed and only reading books about contemporary art.”

His philanthropic interests extend well beyond art, from helping the elderly and the disabled to facilitating blood donations. Smirnov admits that he does not understand everything that he buys, but if he finds a work interesting he wants to learn about it and seeks a meeting with the artist. Artists have become friends, he said, speaking with affection about their frequently difficult characters and noting that female artists are “more stable” than men.

His views on contemporary art are frank. “There is not enough love in contemporary art, there is only professionalism,” he says. “Contemporary art is not the easiest subject to understand. There are often things in contemporary art that one doesn’t even want to look at. In principle, that’s what I do. I don’t try to contemplate. If something is abominable to me, I say it’s abominable. I don’t want to understand how an artist wanted to express his deep thoughts and that’s why he rubbed feces on his face.”

He does not like art that he regards as gratuitously provocative, such as chopping up icons or using obscene language. He cannot brook the Paris-based artist Petr Pavlensky (b. 1984), best known for shock actions, such as nailing his scrotum to Moscow’s Red Square or cutting his ear off in protest to polical activists being confined in a psychiatric hospital. The same goes for Russia’s Pussy Riot group. They are popular in the West, he said, because “the West is narrow minded”, hung up on misguided tolerance.

“It’s a trap,” he said. “Freedom is the main thing that God gave us, but people have gone crazy. They have forgotten about freedom and responsibility and have totally lost all bounds,” says Smirnov, who argues that not understanding this unbridled freedom can lead to moral slavery. “It doesn’t happen when someone physically conquers you. It can happen morally when you enter into servitude, once you have nothing left inside you. It all begins with positive rationales.”

The Foundation of Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantine Sorokin

Art 2010+. An Exhibition of Works Donated by Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantin Sorokin