A vaccine against cynicism

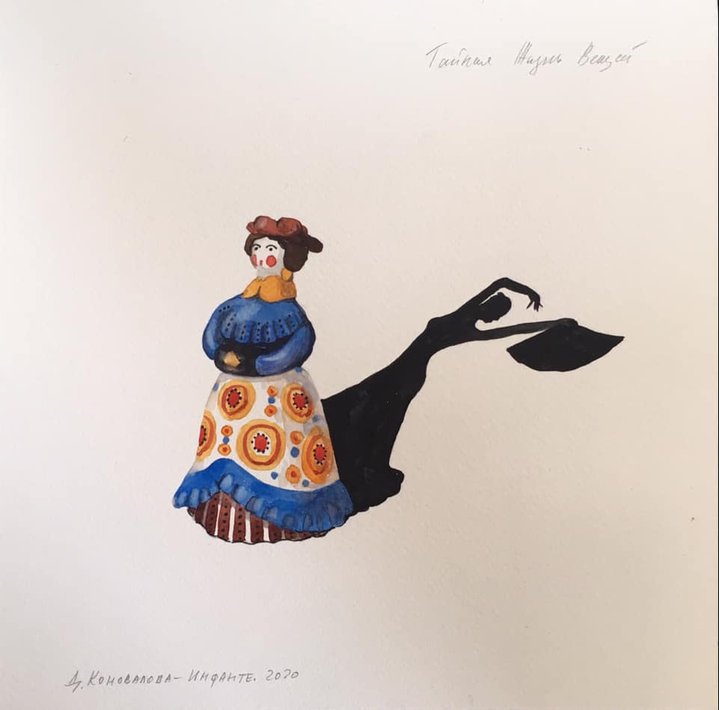

Irina Korina. Cabinet architecture. Vase for pencils, brushes and dry branches. Сhamotte. 10x13 cm

The Facebook marketplace ‘The Ball and The Cross’ (‘Shar I Krest’) has become the talk of the town for aficionados of Russian art throughout the lockdown months. Art historian and art assessor Ulyana Dobrova, who plays an active part in the group, as both seller and buyer, reflects on impact on the Russian art market.

Before the quarantine, the Russian art market had been on life support. Collectors barely outnumbered dealers. Each request for an artwork led to a long chain of middle-men, which pushed purchase prices up to record levels which never materialized. Since the beginning of the 2014 war in Ukraine, collectors have had less money to spend on acquisitions; the popularity of Russian art abroad has fallen and control over the export of artworks has tightened. As a result, the number of deals hovered around zero.

The pandemic, one might expect, would only deepen the malaise. Who stocks up on art like toilet paper during a pandemic? But then, dealer and collector Maksim Bokser created ‘The Ball and the Cross’ (‘Shar I Krest’ or SHiK), inviting his friends to buy and sell art at low prices to support artists in a fun, no-pressure environment on Facebook. The group became a Russian analogue to British artist Matthew Burrows’ ‘Artist Support Pledge’. Since its birth in March, SHiK has grown to 9,000 participants, seen roughly 20 million roubles in sales, held two charity auctions, spawned copycats (such as St. Petersburg’s ‘Arena’, Ukraine’s ‘Salt and Pepper’ and Uzbekistan’s ‘Art Bazaar’) and acquired an army of detractors.

Some of SHiK’s skeptics take issue with its purported philanthropic motives. “How can we speak of mutual aid if artists are required to sell their works at a discount?” they ask. Art market insiders fret that SHiK will lead to a mutation of that market and freeze prices at 20,000 rubles (ca. $276), the maximum price limit for the group. Their fears, however, are misplaced. The sales reflect what analysts would call “liquidation prices”, when a work is sold for lower than its market value, in order to put cash in the artist’s pocket as quickly as possible. Typically, this price is evaluated at 20 percent of the market value. Outside the bounds of SHiK, away from the “sharks” that lurk in the group, the same works are already selling through private channels for five times the price.

Another set of critics take issue with the content on display, which they see as unforgivably out-of-step with the reigning trends in contemporary art. As Roman Minaev, a professor from Moscow’s Rodchenko School, wrote on Facebook, “It’s good that groups like ‘Ball and Cross’ are appearing. They let us see what the untrained eye cannot see: the level of contemporary art. There’s nowhere left to fall. This is the bottom.”

To understand the selection criteria, one must turn to the recent exhibition of Bokser’s personal collection, ‘The Dreams of a Collector’, which opened in Moscow’s private In Artibus Foundation in late March, but which was immediately forced to change its format because of the pandemic. Viewers can see the show one person at a time, and only by appointment. Bokser’s collection is one of the best in Russia, ranging from the Symbolists to the Russian Avant-Garde and cutting-edge contemporary art. Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) can be displayed on the same wall as Ivan Lounguine (b. 1979), based on nothing more than the deeply personal link between their works and the collector.

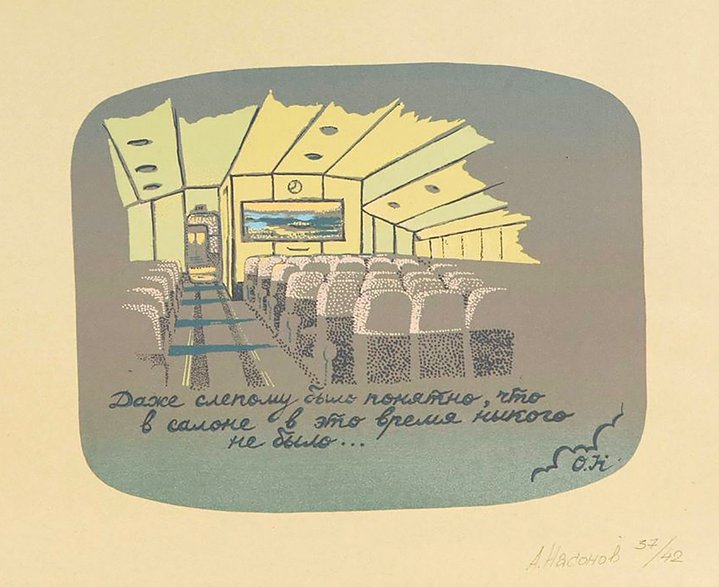

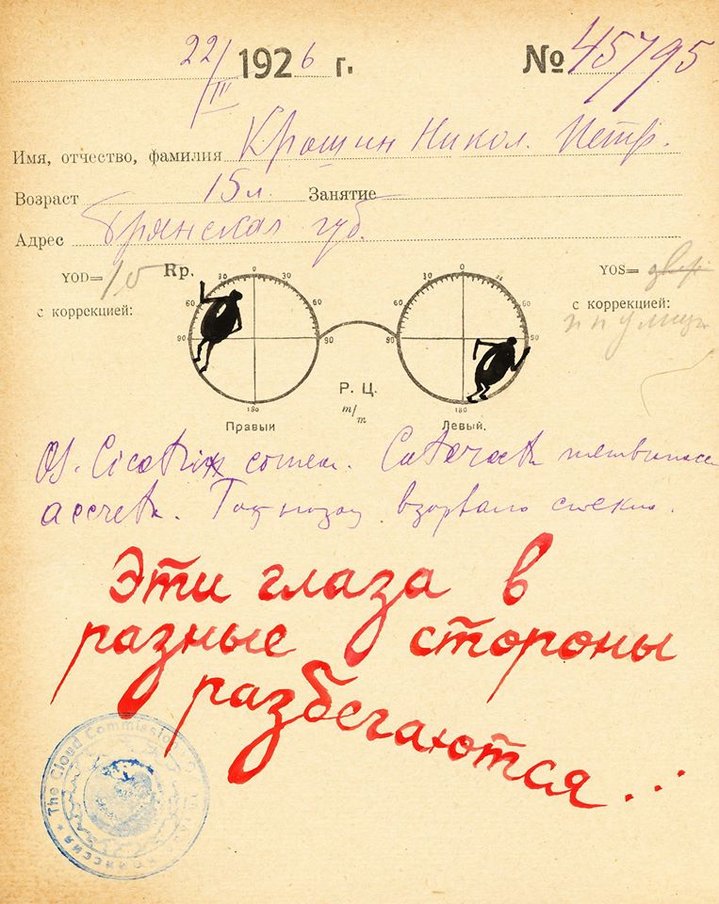

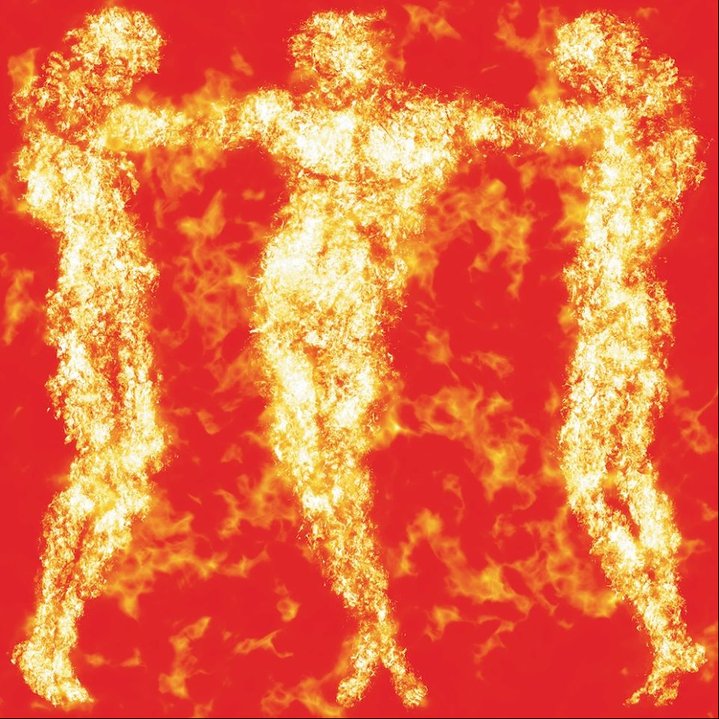

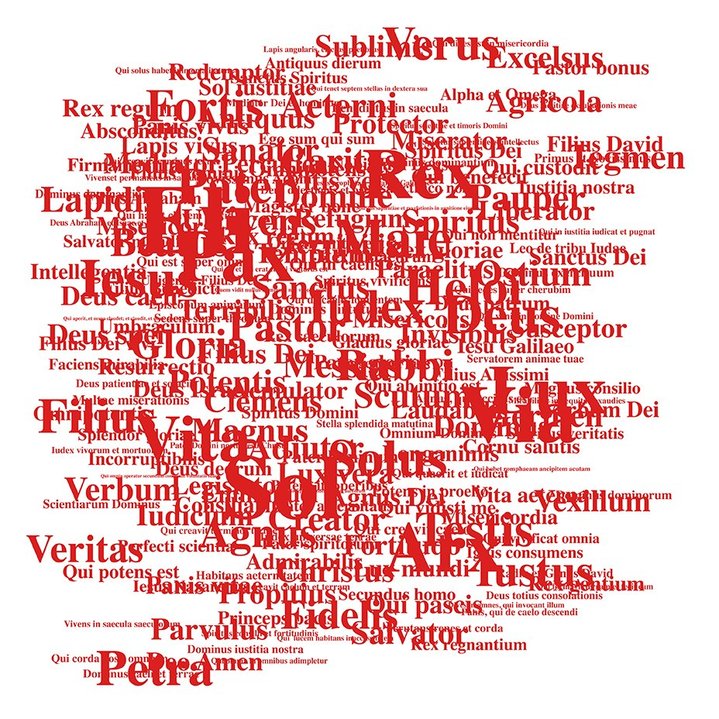

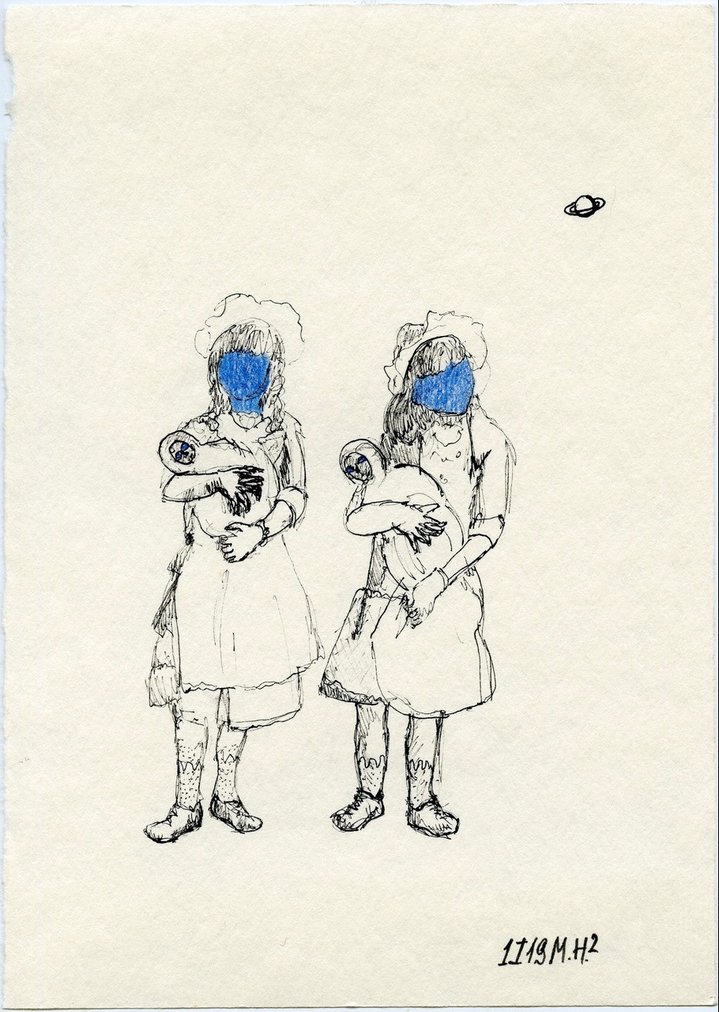

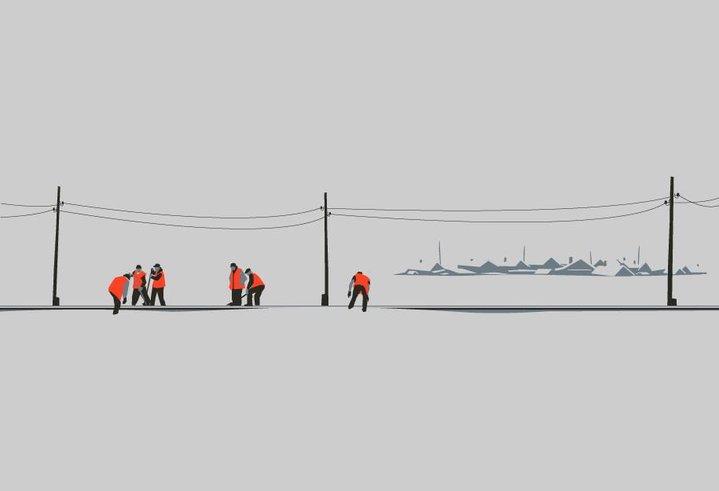

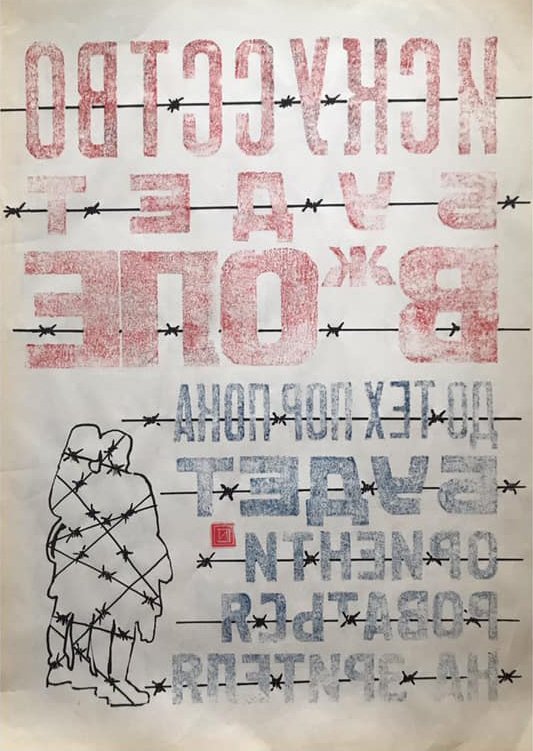

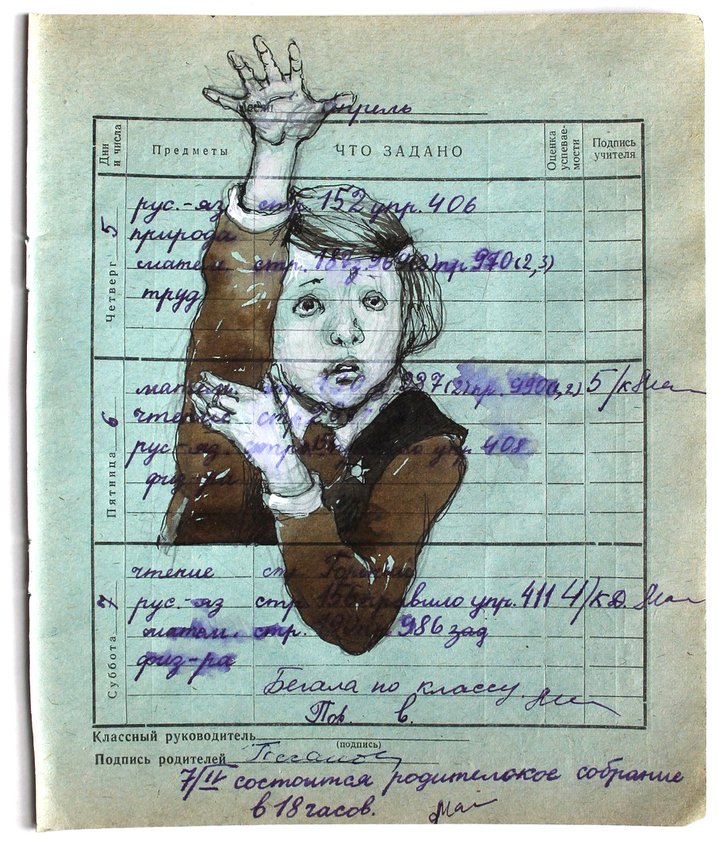

Submissions pass through an initial filtering process that removes more than half of all entries. Many of the pieces that make it through are small graphic works, or found objects such as bills, newspapers, and scraps filled with text and images by Marina Skepner (b. 1980), Rivka Belareva (b. 1978) and Kirill Danelia (b. 1968). Amongst the participating artists, there are many whose works never sold for more than 20,000 rubles, in any case. Talented graphic artists and painters whose work never appealed to the taste of young curators, have suddenly emerged from oblivion and ended up in the same online gallery as such stars as poet and conceptual artist Lev Rubinstein (b. 1947), Aidan Salakhova (b. 1964), Arkady Nasonov (b. 1969) and Gosha Ostretsov (b. 1967). Big-name contemporary artists have turned to making small-scale works specially for SHiK, as epitomised by Irina Korina’s (b. 1977) ‘Cabinet Architecture’ series displaying fairy-tale, constructivist castles of clay meant for arranging flowers and pens on one’s desk. On SHiK, old media is in vogue and the group rejects the cynicism of contemporary social media. And what if low prices do not mean dumping, but rather a vaccine against the virus of cynicism?

The Ball and the Cross (Шар и Крест)