A cryptic man of many sides

Russian-born collector and former art dealer Alex Lachmann has a diverse taste for art. He has amassed a wealth of artworks by blue-chip Russian and international stars and Soviet underground artists of the 1960s in his London home.

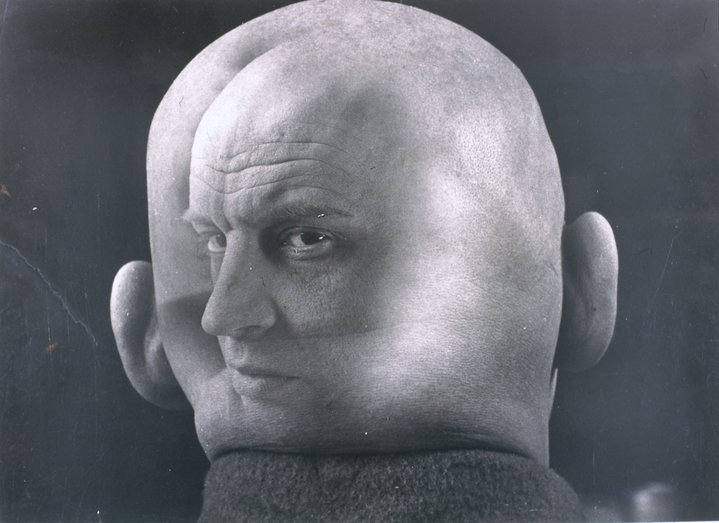

Russian collector and former gallerist Alex Lachmann lives part of the year round in London’s Belgravia in one of very few stylish contemporary developments among otherwise stucco fronted Georgian terraced villas and embassies. His apartment is hidden behind high walls, in a discrete, private mews, with landscaped courtyards and an Andy Goldsworthy slate relief leading to the entrance, a hint of what you might find inside. His grandfather and mother were both architects, he has an eye for space with echoes of constructivism and this is the perfect backdrop for his enviable art collection, with vast ceilings and tall doors. He had it designed so that his study is in the middle of an open space serving as a corridor, guests sit in the half dark and he sits opposite in front of a window, cast into the shadows you cannot see his face easily, art trading is like poker, probably it used to help him to get the best side of a deal. To the left his library, everywhere paintings on the floor. “They come back from museum exhibitions and I don’t have anywhere to hang them,” he explains.

Lachmann discovered his first real love of photography back in the 1980s and it is evident everywhere today; custom-made floor to ceiling shelving on which his collection of masterpieces of Soviet avant-garde photography sits and the display is full up. “I probably should not be buying any more,” says Lachman, then he showed me with palpable enthusiasm a Nan Goldin photograph sitting by his front door, still wrapped in bubble paper, he had just bought at auction. That is the problem real collectors have is they cannot stop, collecting is a passion that knows no end.

After a stint trading in icons in Soviet Russia (a complex activity only half-legal and attracting disapproval, for many Russians icons are still only objects of prayer, God forbid, never for sale), Lachmann left Russia for good in 1981. As a young immigrant dealer in the 1980s, he was surrounded by German photography in Cologne at the time a centre for contemporary art. He quickly saw the stylistic closeness between German and Russian photographers from the 1920s and 1930s, the Bauhaus was a melting pot of the two. He trained his eye on the Germans and the dynamics of that market, getting a measure of the taste of the collectors then, what they were looking for. But his own heritage was a greater draw and he gradually amassed several collections of avant-garde Russian photography, staging first ever solo shows in his commercial space. There was Georgy Petrusov (1903–1971), Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), Boris Ignatovich (1899–1976) and Arkady Shaikhet (1898–1959) and he showed works that even museum curators had not seen before. By the beginning of the 1990s, he sold up a large part of the collection to Peter Ludwig in a major deal that helped to set him up and build his business to the next level.

We talk about how Russian collectors today, unlike Americans, are not focussed on photography, but how to inspire them to collect when there is so little material. ‘It is also the problem for the Russian avant-garde, if a collector asks you to find a painting by Rene Magritte, you can find some great things to show, but if you are asked to find a great piece of Russian Avant-garde art or a photo by Rodchenko or one of his contemporaries, it is nearly impossible. “It is down to history, [in the Soviet times] there were no galleries in Russia, there was no market.”

I mean to ask him when and how he moved from being a dealer to a collector, but that is a well-trodden path and the answer is obvious to me: successful dealers always manage to eventually gather up works - stock - and they keep on holding the best works they find as long as they can. It is a process that takes some time although with the fast rise in the fortunes of the Russian art market in the noughties, this was accelerated for many dealers in the field at that time. It is well known that Alex Lachmann is especially close to Russian and European mega collectors. There is no doubt that he has been a central figure in the Russian art market over the past three decades.

What his collection has become for him today, it is easy to see: It is an inseparable part of his life, it represents for him something of who he is. There is no space in his rather vast apartment where there is not a work of art or a painting crammed into a corner or sitting in the middle of the floor, the kitchen has shelving high above the sink with pieces of Russian revolutionary porcelain. Not your best china to bring down and eat from once a year, but porcelain to admire, it is for decoration only. We don’t talk about it, but Alex Lachmann’s expertise on Soviet porcelain - as in other fields in which he takes a professional interest - is impressive, if not even legendary. He is someone people go to when needing advice (unless he is planning to bid on the same lot at auction as you in which case you might not get the real answer - collecting is a competitive sport and has few rules other than the best man wins).

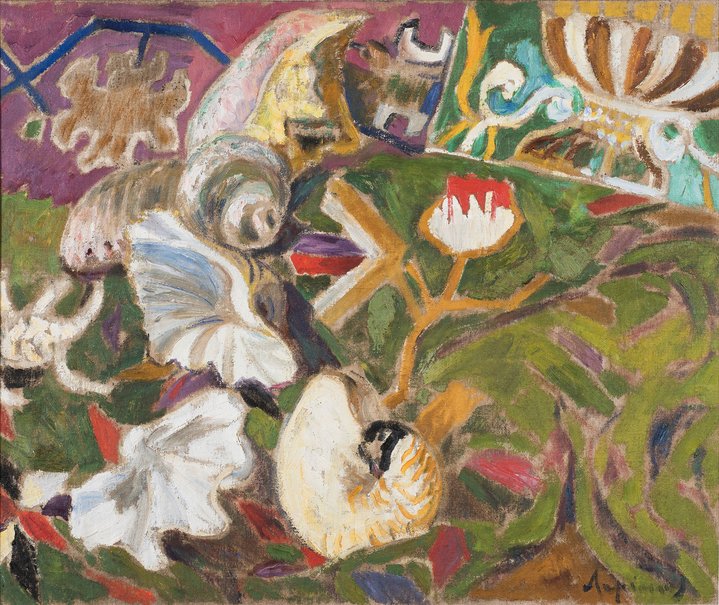

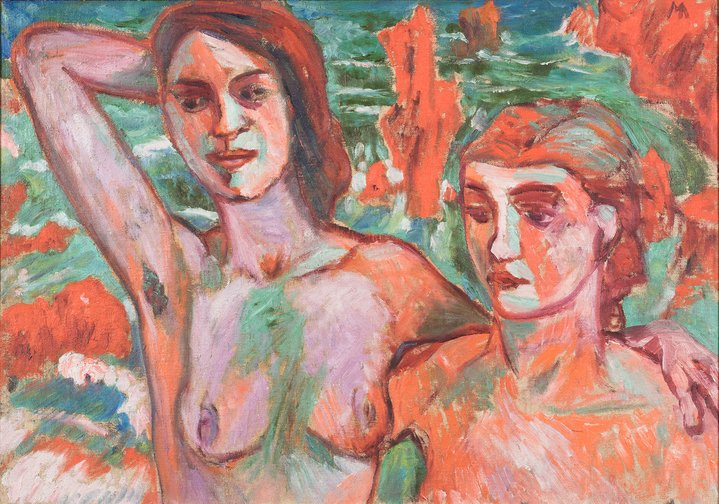

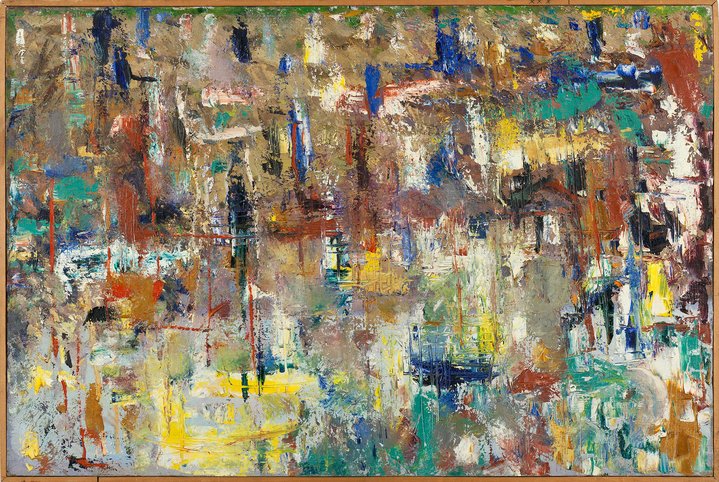

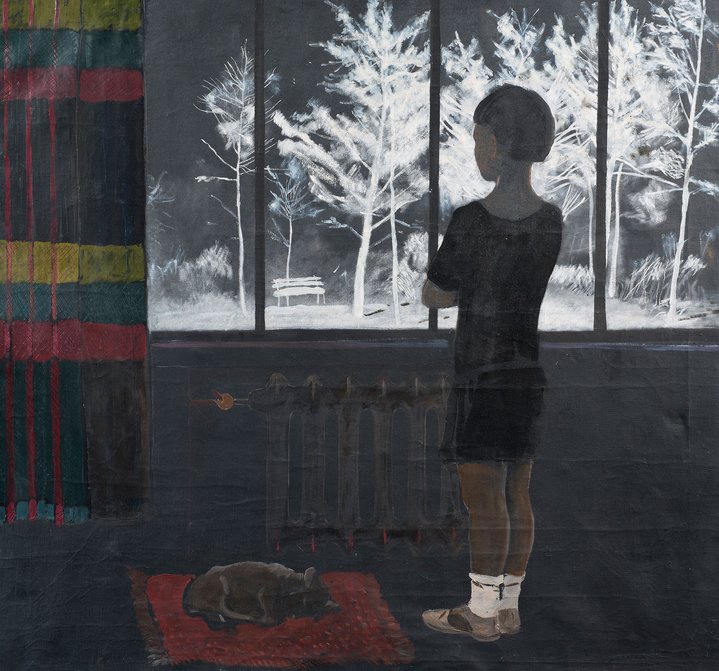

His Russian contemporary art heroes are Ilya Kabakov (b.1933) and Erik Bulatov, (b.1933) he owns ‘Welcome’, one of the few large-scale paintings Bulatov did in the 1980s, when he found his artistic maturity. Lachmann has less interest in Russian art created after perestroika which he feels in general lacks substance. For him, periods of enormous social change like in the early 20th century and later during perestroika have produced the best art. “When a society is at its strongest then you get powerful art, it was Germany in the 1920s, Russia during the revolution and perestroika.” His apartment is dominated by Russian avant-garde art, however, everywhere you look he has works by international names, he says, “my interests have many sides.” There are sculptures: a full-size human figure by Antony Gormley on his balcony (“My neighbours think it is a bodyguard.”); two works by William Kentridge (b.1955); a Tracey Emin (b.1963); a painting by Neo Rauch (b. 1960), several works by Günther Uecker (b.1930). Among the Russians, he likes the generation of the 1960s, especially Dmitry Krasnopevtsev (1925–1995) (he has the record work I sold him while at Sotheby’s in 2007 hanging by his desk which once belonged to a French diplomat), Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016), Vladimir Yankilevsky (1938–2018) and Ivan Chuikov (1935–2020), and the generation of the 1990s such as Konstantin Zvezdochetov (b.1958), and Oleg Kulik (b.1961). Among photographers he reserves most praise for Ukrainain-born Boris Mikhailov (b.1938) whose art photography was particularly inventive and later defined the post-soviet landscape.

“The language of Russian contemporary art is not so understandable,” he says breezily, “there is a big difference, if you compare it with China, the language of Chinese contemporary art is understandable for the West. Russians also tried to make art to appeal to Western collectors, but in Russia artists make work which addresses problems in Russia, they try to play with these problems, ones which have no easy answers, probably mostly about Russia’s absolutism. In the West artists address global problems and they are interesting for everyone.”

Lachmann still keeps his former gallery space Cologne and divides his time between that city and London, but he also has an apartment in the centre of Moscow. “I like Moscow very much, it has become a great city especially for culture, there is a new wind blowing.” He refers also to large-scale initiatives such as the Garage Museum of Contemporary Culture and GES-2, due to open later this year. His apartment in Moscow holds mainly Russian art, we talk about how hard it is to import art into Russia from abroad, “if more art comes into Russia, Russia will be a richer country culturally.”

We speak about the challenges faced by international galleries and collectors buying Russian art, or art inside Russia. According to current legislation, there is no specially reduced tariff for art and antiques in Russia, which means it is out of step with the international community; it is operating at a disadvantage. Any state support ought to be focussed on this and legislative measures to encourage trade, rather than any initiatives to support galleries “the State must not interfere in this process, that is precisely what happened in the Soviet times”. It is about supporting the infrastructure, and lowering taxes, he points out that in most countries there is a reduced VAT for the purchase of art, where in Russia this does not exist, but he continues, “if you make a low tax, people will pay it.”

I ask him about what the future holds and, it turns out, he is full of ideas: he is exploring the possibilities of founding a crypto museum for his collection. “This type of museum is easier to manage in perpetuity,” he says. I think of how a collection is worth more than the sum of its parts, it is a unique cultural organism which is formed perhaps by an individual taste, but which also has social value. Assembling a collection during a certain epoch can reflect values of the times, which shine a light on that generation and its artistic legacy; collecting is an activity which occurs in a certain time and place, through its prism we can uncover interesting stories which perhaps have wider meaning. We are living in a time when museums are being questioned, the roles of the state museum and the privately funded museum are being re-examined. And the blockchain generation will likely decentralise cultural assets further in a way we have hitherto not seen. Crypto museums keep the art together but the museum itself is virtual which means it is accessible, it can be used for educational purposes. I think that it is a concept very in tune with our times.